Policy Q&A: How Boston Is Implementing Solutions to Protect Young Children from Extreme Heat

Paula Gaviria Villarreal, of Boston's Office of Early Childhood, discusses new initiatives to keep young children cool and shares how other local governments can take steps to minimize the effects of extreme heat.

In our Policy Q&A series, we’re featuring a diverse array of perspectives on the many ways that science, community expertise, and lived experience can inform policy and program design to support healthy development during the earliest years.

Like many cities around the country, Boston is increasingly affected by extreme heat. Between 2010 and 2020, the city experienced more hot days than any decade in the previous 50 years—and this trend is projected to continue.

The City of Boston is now committed to taking action, with a resiliency plan to prepare its people, communities, and infrastructure for hotter summers and protect the public from the effects of extreme heat. But while the dangers of excessive heat to certain groups, such as older adults, are well-known, its effects during pregnancy, infancy, and childhood typically receive less attention in such plans.

To address this gap, the City of Boston’s Office of Early Childhood partnered with the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University to host the Boston Extreme Heat and Early Childhood Roundtable series last spring. The series was inspired by the Center’s working paper, Extreme Heat Affects Early Childhood Development and Health, which underscores how excessive heat can affect young children’s developing biological systems—with implications for their lifelong health and well-being.

The Roundtable convened a group with a range of expertise, from city officials and pediatricians to caregivers and community members with lived experience. Over the course of three sessions, the participants focused on understanding the science of extreme heat and early childhood, exploring solutions in other cities, and developing action plans for Boston. The Office of Early Childhood is now implementing a variety of these initiatives to help keep young children and their caregivers cool.

In this Q&A, Paula Gaviria Villarreal, Child Care Analytics and Program Director for the Office of Early Childhood, who is leading implementation of these solutions, shares how Boston brought diverse stakeholders together to launch the work, how the initiatives will reach young children and caregivers, and how other local governments can take steps to minimize the effects of extreme heat.

People don’t tend to think of Boston as a hot place. Why did the City identify extreme heat—and its impact on young children—as a priority policy issue?

We’re experiencing a rise in temperatures every summer, and Boston was never designed to withstand this heat. So, there’s been an awareness from the Mayor’s Office that, as summers get warmer, we need to be better prepared as a city to keep our residents safe.

Mayor Michelle Wu also created the Office of Early Childhood in 2022. Initially, our office primarily worked on issues related to childcare and supporting childcare providers. But early childhood is so much broader than that, and we wanted to expand the work. After meeting with the Center on the Developing Child, our Director, Kristin McSwain, learned there was an upcoming paper on extreme heat and children. She was really excited by this opportunity, because while there was already a lot of work around extreme heat happening in Boston, there wasn’t a specific focus on this population.

To launch this work, the Office of Early Childhood brought together a range of city departments, as well as caregivers and other experts. Why was it important to have this diversity of perspectives and expertise at the table?

City government can feel large, and there’s often a lack of communication between departments. We wanted the Roundtable to be an opportunity for all these different departments—many of whom are already doing work related to extreme heat, climate change, and health, and could benefit from all this new knowledge around young children—to come together, learn from each other, and collaborate and coordinate on the work.

For example, we had representatives from the Boston Public Health Commission, the Environment Department, the Mayor’s Office—including policy and partnerships teams—and the Office of New Urban Mechanics, who creatively address issues from a design and urban planning perspective. We also included local pediatricians and parents of young children from a community organization in East Boston, an area that has been identified as a heat island. We thought having that caregiver perspective would be really valuable—because they’re the constituents—and they were very informative to our work.

The first session focused on understanding the science of extreme heat and its impact on early childhood development and health. How did this scientific foundation contribute to the Roundtable’s success?

“Learning the actual science—that not only is there a real impact on children, but that the way children experience heat is completely different from someone who is older—created a real switch in everyone.”

The way that Dr. Burghardt [Chief Science Officer at the Center on the Developing Child] presented the evidence was really impactful. Some people might have been a little skeptical at first, because most of us know about older adults having heat strokes, but we don’t tend to see the impact of extreme heat during pregnancy and early childhood in that way. But learning the actual science—that not only is there a real impact on children, but that the way children experience heat is completely different from someone who is older—created a real switch in everyone. We all understood the need to prioritize this population during extreme heat emergencies.

The working paper underscored that the impact of heat is often greatest in low-income communities and communities of color, where decades of discriminatory zoning and lending practices have led to the creation of urban heat islands. Similarly, the City of Boston has found that formerly redlined areas can be 7.5°F hotter during heat waves than the rest of Boston. How did you keep these inequities in mind when considering solutions?

The heat islands in Boston tend to be neighborhoods with a high population concentration, less green space and tree shade, and more buildings and roads. That urban design makes it much warmer. We’ve found that these areas also tend to have residents with lower incomes, more Black and Brown residents, and lots of children living there. We wanted to focus on these places—where many of our family childcare providers are also located—so that we can reach the people who are not only experiencing more heat than the rest of Boston but also may have fewer resources to cool off.

Boston is now actively implementing solutions to reduce the impacts of extreme heat on young children. Could you describe these initiatives and how they will be rolled out in Boston neighborhoods this summer?

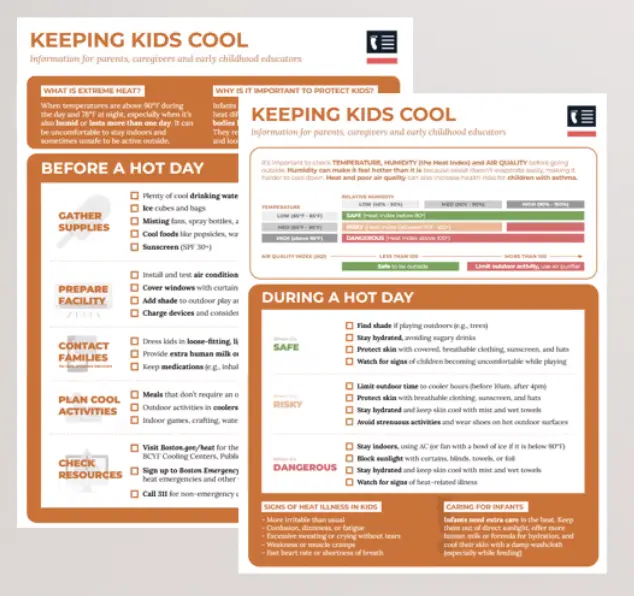

We’re calling the overall work “Keeping Kids Cool,” and there are three specific workstreams: cool public spaces, cool childcare facilities, and cool homes.

There already were cool public spaces in Boston where people could go during heat emergencies—such as a library or Boston Housing Authority location. But what we learned from our parents at the Roundtable was that when you have a young child, you need something to do while you’re sitting in that cool space. So, we’re coordinating with public spaces within Boston’s heat islands to make sure child-friendly programming is available throughout the summer and specifically during heat emergencies. We’re also distributing “Made to Play” kits with developmentally appropriate activities that parents can use to keep kids entertained. And we created maps that identify the cooling resources within every city neighborhood—like splash pads or fountains—that families can easily access.

In terms of cool childcare facilities, we’re partnering with 26 family childcare providers on a pilot called the Extreme Heat Action Plan and Indoor Temperature Sensors. We hypothesized that within the city’s heat islands, many of the childcare spaces—where kids spend most of their day—actually reach high temperatures before an official heat advisory or emergency is declared throughout Boston. So, each facility will receive a temperature sensor that will help the providers understand their own space, help us measure temperature in these heat islands, and help us identify how we can support these providers, such as connecting them to state programs that make air conditioning installation more affordable. We’re also making Extreme Heat Action Plans available in different languages to all family childcare providers throughout the city. This document explains how to prepare the facility for heat emergencies, what resources exist, what activities providers should avoid for infants or toddlers during heat, and more. We want providers to have this up and available in the space, just like they already display CPR or other important instructions.

KEEPING KIDS COOL

The third initiative is communication around cool homes. This one is particularly exciting to me, in the sense that it can have the biggest reach without a lot of effort. We realized that heat alerts from the City don’t necessarily reach many families. They really get information from community organizations that they already trust and go to for other services. So, we reached out to community organizations and invited them to serve as “neighborhood heat champions.” They’ll take the information that the City creates on heat advisories and emergencies and share it with families through the channels that they already use—like WhatsApp or Facebook. This will help us reach more families and keep them safe. We’re also working with existing City of Boston communication channels to include advice that is specific to infants, young children, and pregnant people within those heat alerts. And starting next year, we’ll send out a printed Summer Weather Guide that also includes information on keeping this specific population safe. Boston has already sent a Winter Weather Guide to every address in the city for many years—but now that we’re experiencing more extreme heat, we saw the need for a summer guide as well.

How are you tracking the impact of these efforts?

We’re collecting data during the childcare provider pilot in two ways: quantitative data on temperatures from the heat sensors and qualitative data from regular check-ins with the providers. While respecting the children’s anonymity, we’ll be able to gather information like what providers did to keep their spaces cool during heat emergencies and whether they noticed changes in the children’s behavior, like more irritability or fatigue. We’ll also gather feedback on the Extreme Heat Action Plan and learn what was helpful for providers and what we might want to change.

What advice would you give to other local governments and policymakers looking to implement solutions that protect children from extreme heat, particularly lower-resourced communities?

I think it’s very important to engage constituents and families early on—because they’re the ones for whom we design these policies and programs, and they can help us understand if they will actually benefit.

“I think it’s very important to engage constituents and families early on—because they’re the ones for whom we design these policies and programs, and they can help us understand if they will actually benefit.”

I’d also emphasize that this work doesn’t require a lot of new investment. If you think about the three strategies we are implementing now, most of the work was already being done. For example, the City was already releasing heat communications and alerts—it’s just about identifying ways to adapt or include messaging around young children. We also relied heavily on internal and external partners that we already had, such as identifying heat champions from community organizations that had established relationships with the City. Communications, in particular, is very low cost but very high reach.

What makes you most excited about the impact of this work?

Just a year ago, this wasn’t on many people’s radars. Now we have a deeper understanding of extreme heat and children, and hopefully with these initiatives, we’ll be able to create a sense of urgency around the need to focus on keeping kids cool and safe throughout the summer.

I’m also excited to see the work being institutionalized—this isn’t temporary. For example, Boston’s next Climate Action Plan will include a specific focus on young children for the first time. Recently, the City also created a Children’s Council. It’s a space, similar to the Roundtable, where we can share and collaborate across departments on policy and programming that involves or impacts children. One of the Council’s initiatives is specifically focused on kids and climate—so efforts to prepare this population for heat emergencies is something that will be there in the long run.

We want this work to continue—and it doesn’t just have to be about extreme heat. We hope to have future versions of the Roundtable with the Center focused on the impact of air quality and water on early childhood. The Roundtable showed us that if we focus on where young children are spending the most time, we can design policy and programming that reaches our intended population and really has an impact.

The Center on the Developing Child is now partnering with other cities to host future Roundtables on extreme heat and other topics that affect early childhood development and health. To learn more, please contact Susan Crowley, Senior Project Manager, Partnerships and Engagement, at susan_crowley@harvard.edu.

The Center on the Developing Child is committed to elevating a variety of perspectives around supporting healthy development in the earliest years. The views and opinions expressed by Policy Q&A subjects are those of the individual and do not necessarily represent those of the Center.

Additional Resources:

City of Boston

National League of Cities