How Racism Can Affect Child Development

What could our society look like if racial disparities in health and learning outcomes didn’t exist? According to extensive studies, the U.S. would save billions in health care costs alone. The value of realizing the potential contributions of so many people around the world who are impaired by—or die from—preventable chronic illnesses is enormous, and the human costs are incalculable.

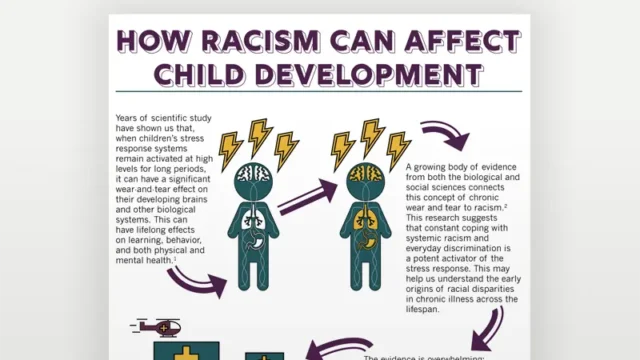

Advances in science are presenting an increasingly clear picture of how significant adversity in the lives of young children can disrupt the development of the brain and other biological systems. These early disruptions can undermine young children’s opportunities to achieve their full potential. And, while they may be invisible to those who do not experience them, there is no doubt that both systemic racism and interpersonal discrimination can lead to chronic stress activation that imposes significant hardships on families raising young children.

It’s time to connect these dots. This infographic explains in basic terms how racism in particular gets “under the skin” and affects learning, behavior, and lifelong health. There is much more to say, but by starting with a shared understanding, we can work together toward creative strategies to address these long-standing inequities.

View Sources

Panel 1

Forde, A.T., Crookes, D.M., Suglia, S.F., & Demmer, R.T. (2019). The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: a systematic review. Annals of Epidemiology, 33, 1-18.e3

Panel 2

Geronimus, A.T., Hicken, M., Keene, D., & Bound, J. (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826-833.

McEwen, B.S. (1998.) Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(3), 171-9.

Panel 3

Williams, D.R., & Wyatt, R. (2015). Racial Bias in Health Care and Health: Challenges and Opportunities. JAMA 314(6): 555-556.

Williams, D.R., Mohammed, S.A., Leavell, J., & Collins, C. (2010). Race, socioeconomic status and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1186, 69.

Panel 4

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2019). 2018 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Rockville, MD. AHRQ Pub. No. 19-0070-EF https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/2018qdr-final-es.pdf

Manuel J. I. (2018). Racial/Ethnic and Gender Disparities in Health Care Use and Access. Health Services Research, 53(3), 1407-1429.

Panel 5

Heard-Garris, N.J., Cale, M., Camaj, L., Hamati, M.C., & Dominguez, T.P. (2018). Transmitting trauma: A systematic review of vicarious racism and child health. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 230-240.

Pachter, L.M., & Coll, C.G. (2009). Racism and child health: a review of the literature and future directions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(3), 255-263.

Clark, R., Anderson, N.B., Clark, V.R., & Williams, D.R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54(10), 805- 816.

Panel 6

Trent, M., Dooley, D.G., & Dougé, J. (2019). The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics, 144(2), e20191765.

Williams, D. R., & Cooper, L. A. (2019). Reducing Racial Inequities in Health: Using What We Already Know to Take Action. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(4), 606.

Panel 7

Collins, C., Asante-Muhammed, D., Hoxie, J., & Nieves, E. (2017). The road to zero wealth: How the racial wealth divide is hollowing out America’s middle class. Washington, DC: Prosperity Now and Institute for Policy Studies.

Weir, K. (2016). Policing in Black & White. Monitor on Psychology, 47(11). Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/monitor/2016/12/cover-policing

Panel 8

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2020). Connecting the Brain to the Rest of the Body: Early Childhood Development and Lifelong Health Are Deeply Intertwined: Working Paper No. 15. Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu