Policy Q&A: The Founder of the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center on How States Can Help Young Children Thrive

Dr. Cynthia Osborne shares the importance of investing in the early years, and why policy is such a powerful tool for improving outcomes in early childhood.

In our Policy Q&A series, we’re featuring a diverse array of perspectives on the many ways that science, community expertise, and lived experience can inform policy and program design to support healthy development during the earliest years.

Over the last 20 years, science has contributed to rapid advancements in our understanding of child development and the importance of investing in the earliest years. We know that responsive caregiver relationships are critical for building healthy brain architecture. And, we must also consider how a wide range of conditions in children’s environments—from access to health care to housing stability—shape not only their brain development, but their lifelong health and well-being.

But how can society best translate that science into solutions? As founder and executive director of the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center (PN-3), Cynthia Osborne, PhD, and her team are dedicated to answering that question. PN-3, a nonpartisan research center at Vanderbilt University, reviews rigorous evidence to determine the state policies most effective at improving outcomes for infants and toddlers. Through resources like their annual Prenatal-to-3 State Policy Roadmap, PN-3 provides lawmakers, agencies, advocates, and academics across the country with evidence-based, actionable solutions to help children thrive from the start.

In this Q&A, Dr. Osborne, also a Professor of Early Childhood Education and Policy at Peabody College at Vanderbilt University, shares the importance of investing in the early years, why policy is such a powerful tool for improving outcomes in early childhood, and how states can use PN-3’s resources to most effectively and efficiently create change for young children and their families.

You founded the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center in 2019. What were your initial goals?

We wanted to focus on the prenatal-to-three developmental period because the science was just overwhelming in terms of how important this period is for children’s healthy development. Of course, the Center on the Developing Child was the lead voice in helping us all understand this. Prenatal to age three is the most rapid and sensitive period of development. It’s also a time in which the brain and all our body’s systems are highly impacted by the environment we’re in. And this has lasting impacts on our health and well-being. So, if we start early, we can make a bigger difference in how healthy children develop. And if we delay, it’s much more difficult, it’s much more costly, and the outcomes are just not as robust as they could have been.

So, our mission was to build on that science of the developing child that told us how important this period of development is and say: What are the state-level policies that create that environment in which children can thrive from the start? That was our whole mission, and it’s what we continue to do.

Why is policy such a critical part of making change in the early childhood space?

“The research is really clear that we need a system of support for children and families.”

Children don’t live in isolation; they live within a family unit and within their community. So, to foster an environment in which children experience safe, stable, nurturing relationships, it requires thinking about their parents, too. Parents need jobs that are supportive of their ability to both work and raise a family, they need physical health and mental health resources, and they need help to best nurture their children in the earliest years.

The research is really clear that we need a system of support for children and families. That’s a combination of broad-based economic and family supports—like tax credits and health insurance—as well as more targeted interventions to meet the specific needs of parents, such as early intervention services. And that combination requires thinking systemically. It requires thinking from a policy level, not just a program level.

There’s increasing recognition of the need to extend beyond traditional “children’s issues” to include a wide range of policy domains that shape children’s environments, from economic security to housing. Could you talk about the diversity of policy sectors that play a role in children’s development?

When we were getting off the ground in 2019, the field was really focused on childcare and on programs targeted toward the child and parent dyad, such as home visiting. Those are really important for helping to meet families’ needs. But we also know that physical and mental health impact parents’ ability to provide nurturing relationships with their children. We know that financial resources, food security, and housing stability all impact the stressors on a household. So, we wanted to take a broader, more holistic view of what a system of support looks like.

Many of these programs that we think of as traditional economic security programs actually impact health outcomes. For instance, one of the most effective programs at reducing adverse birth outcomes is increasing the minimum wage. So, this idea that there are only health policies or only economic-support policies or only early learning policies—the research says that they’re all related. And from a family’s perspective, they need that system of support to meet the wide range of needs we all have when raising children.

We continue to look at a broad range of policies and programs that have been rigorously evaluated for their impact. As one example, we recently added community-based doulas, who provide services throughout the prenatal, delivery, and postnatal period to facilitate positive outcomes for moms and babies.

PN-3 focuses specifically on statewide policy. Why is implementing policy at the state level such a powerful approach?

In our political system, states have huge latitude in how they implement programs and the level of generosity. And states can do things that the federal government has decided not to do, such as offering a paid family leave program.

“State policy is where the variation lies. But it’s also where the energy is—and where we can make sure all children have what they need to get off to a healthy start.”

As such, for a family with lower income, where they give birth is the major predictor of the level of resources the family will have. For example, we do a simulation that shows that a mom with an infant and toddler who gives birth in Colorado has over $54,000 a year in annual resources to provide for herself and her two children. If she gives birth in North Carolina, she has just over $20,000 in resources—based on state policy decisions.

So, state policy is where the variation lies. But it’s also where the energy is—and where we can make sure all children have what they need to get off to a healthy start.

PN-3 grounds its work in rigorous evidence. In your view, what is the role that science plays in helping to determine effective policy? And how do you bring science together with community expertise and the lived experience of caregivers raising young children?

“We realize that data-driven information is only part of the policymaking process. We know that lived experience and community voice is hugely important as well.”

We made the decision early on that, as researchers, we would always look at what the evidence tells us. If a state has scarce public dollars and they want to spend them as effectively and as efficiently as possible, starting with the evidence of what works is a wise approach.

At the same time, we are very much aware of how limited the evidence base is. It relies on the fact that someone thought the policy was important enough to evaluate and had the resources to evaluate it rigorously. In particular, we find that the evidence base doesn’t speak to issues of equity very well. It doesn’t tell us what may work well at a community level but hasn’t been tried at scale.

So, we realize that data-driven information is only part of the policymaking process. We know that lived experience and community voice is hugely important as well. That’s why when we work with states, we often team up with advocates, who are very good at bringing both the head and the heart together. It’s also true that those who are the target of benefits and services are not always listened to when programs are being designed. So, although we don’t say something is effective unless we can show a causal link, we’re always reading the literature that’s been done in a qualitative way to better understand the lived experience and the implementation challenges.

The annual Prenatal-to-3 State Policy Roadmap guides state leaders on the most effective investments to help children thrive from the start. How does PN-3 evaluate policies to create the Roadmap? And how can policymakers and other leaders best use it to guide change in their communities?

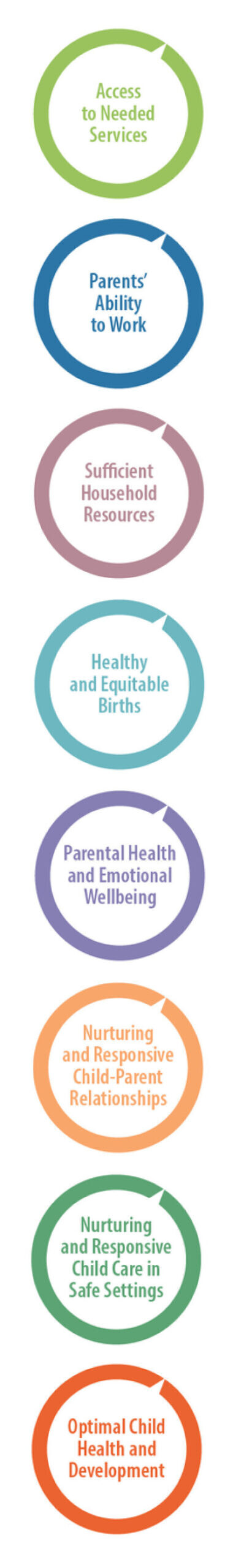

We started with the clear goal of helping states to create the conditions in which children thrive from the start. And science tells us really clearly what that environment needs to look like. So, we operationalized the science of the developing child into eight goals—if we could provide these sorts of things for every family, children could really thrive.

From there, we wanted to identify the policies that states could implement to impact those eight goals. We want to be as evidence-driven, non-ideological, and nonpartisan as possible. So, we didn’t start with any policy in mind. We started from scratch and reviewed dozens and dozens of existing policies and hundreds of the most rigorous research papers to identify the 12 policy solutions that have a strong causal link between implementation at scale and outcomes. Then, for each of those 12, we provide information on the nuts and bolts of the policy: How does it work? How is it funded? Who does it serve? And what does the evidence say about the benefits for families?

In the Roadmap, we then track how states are enacting or implementing these policies. We also have a handful of outcome indicators linked to each goal, such as infant mortality rates or food insecurity. States can use this data to prioritize where they may want to focus their attention.

But what sets the Roadmap apart from other great resources that can tell you how families in your state are doing is that we want to tell folks how they can do better. So that’s where they can find the policies that are aligned with that goal and see what the evidence says about how they can actually start to make a difference.

How have you seen states successfully apply the Roadmap’s insights to improve policy for young children and caregivers?

We try to make the Roadmap as accessible a resource as possible, but we know we also have to bring it to life. So, in addition to releasing the Roadmap, we also provide a lot of direct support for states in implementing those policies.

For example, advocates in one state asked us to perform a benefit-cost analysis to make the case that an earned income tax credit was both good for families and good policy for the state. They were able to use that analysis when walking the halls to say, here’s what the research shows: a four-to-one return. And the bill that they got introduced recently got heard and was voted positively out of one chamber.

Similarly, we worked with another purple state on how they spent their childcare dollars, and we were able to show how many more families are able to work and the benefits that it has for families and children, both in the short and long term. The advocates worked closely with their business community to bring this report to lawmakers and the governor’s staff. The policymaking process is very long and complex; there’s never one thing that puts it over the top. But they credit this information as being influential in helping the governor decide to expand their childcare funding.

PN-3 recently released its 2025 Roadmap. What are a few highlights this year?

Since we started in 2019, we’ve seen huge progress across so many states. But this was a slower year in terms of actually enacting legislation. Part of that is driven by the uncertainty at the federal level about what changes in Medicaid and SNAP [the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program] are going to mean for state-level budgets. We don’t know the answers yet either, but we were able to provide some guidance to states on the potential implications.

“Advocates and policy leaders can use this tool to really understand what changes would mean for families.”

At the same time, we did see some progress this year, including a handful of states making their earned income tax credits and minimum wages more generous, as well as efforts to make childcare more affordable. We also saw a large increase in the number of states that have determined to use Medicaid to cover doulas. One exciting note about this year’s Roadmap is we were able to illustrate—in a very interactive way—how state policy choices interact to create resources for families.We have a stylized example family of a mom, Lina, with an infant and toddler, and we show how the resources that she has to provide for her family vary across every state. So now you can look at how your state compares to every other state. You can simulate policy changes over time: What if our state increased our minimum wage? What if we offered paid leave? Advocates and policy leaders can use this tool to really understand what changes would mean for families. And we’ll continue to build that tool out for different family structures and more policies going forward.

Looking ahead, what new policy approaches most excite you in terms of their potential to support young children and families?

One of the biggest areas we need to learn more about is housing. Housing is fundamental to family stability, and yet hundreds of thousands of infants and toddlers don’t have a stable home. Traditionally, housing has been a federal to local policy. But states are now really stepping up to try new things in this space, whether it’s building more housing, making housing more affordable, or helping families who have experienced housing instability. We need these policies to be evaluated so that we can provide states with as clear guidance as possible.

We’re also looking more at guaranteed income programs, child tax credits, and other sorts of cash programs. We know at the federal level, they were very effective at reducing poverty, but it was temporary. States have been figuring out how to replicate that in ways that will also reduce poverty, make families more stable, and improve child outcomes. More needs to be learned. But there’s a lot of energy in this space, and I think that we’re going to learn a lot in the not-too-distant future.

The Center on the Developing Child is committed to elevating a variety of perspectives around supporting healthy development in the earliest years. The views and opinions expressed by Policy Q&A subjects are those of the individual and do not necessarily represent those of the Center.

Developmental Environments

Developmental Environments

Brain Architecture

Brain Architecture