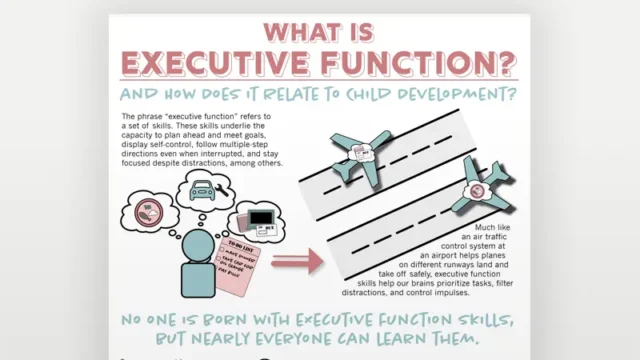

What Is Executive Function? And How Does It Relate to Child Development?

View full text of the graphic

As essential as they are, we aren’t born with the skills that enable us to control impulses, make plans, and stay focused. We are born with the potential to develop these capacities—or not—depending on our experiences during infancy, throughout childhood, and into adolescence. Our genes provide the blueprint, but the early environments in which children live leave a lasting signature on those genes.

This signature influences how or whether that genetic potential is expressed in the brain circuits that underlie the executive function capacities children will rely on throughout their lives. These skills develop through practice and are strengthened by the experiences through which they are applied and honed. Providing the support that children need to build these skills at home, in child care and preschool programs, and in other settings they experience regularly is one of society’s most important responsibilities.

Being able to focus, hold, and work with information in mind, filter distractions, and switch gears is like having an air traffic control system at a busy airport to manage the arrivals and departures of dozens of planes on multiple runways. In the brain, this air traffic control mechanism is called executive function.

More Information on Executive Function

Guide: A Guide to Executive Function

Learn more about the basics of building executive function skills, and learn strategies that can help build them.Working Paper 11: Building the Brain’s “Air Traffic Control” System: How Early Experiences Shape the Development of Executive Function

This in-depth working paper explains executive function works, and gives recommendations for ways that caregivers and policymakers can effectively respond to the science.

This refers to a group of skills that helps us to focus on multiple streams of information at the same time, monitor errors, make decisions in light of available information, revise plans as necessary, and resist the urge to let frustration lead to hasty actions. Acquiring the early building blocks of these skills is one of the most important and challenging tasks of the early childhood years, and the opportunity to build further on these rudimentary capacities is critical to healthy development through middle childhood and adolescence. Just as we rely on our well-developed personal “air traffic control system” to make it through our complex days without stumbling, young children depend on their emerging executive function skills to help them as they learn to read and write, remember the steps in performing an arithmetic problem, take part in class discussions or group projects, and enter into and sustain play with other children. The increasingly competent executive functioning of childhood and adolescence enable children to plan and act in a way that makes them good students, classroom citizens, and friends.

Children who do not have opportunities to use and strengthen these skills, and, therefore, fail to become proficient—or children who lack the capacity for proficiency because of disabilities or, for that matter, adults who lose it due to brain injury or old age—have a very hard time managing the routine tasks of daily life. Studying, sustaining friendships, holding down a job, or managing a crisis pose even bigger challenges.

Correcting Popular Misconceptions of Science

The fact that young children have a difficult time with self-control, planning, ignoring distractions, and adjusting to new demands is hardly news to the adults who care for them. It is not widely recognized, however, that these capacities do not automatically develop with maturity over time. Furthermore, it is even less well known that the developing brain circuitry related to these kinds of skills follows an extended timetable that begins in early childhood and continues past adolescence and that it provides the common foundation on which early learning and social skills are built. Based on this new understanding, the following common misconceptions about the development of executive function skills can be laid to rest.

Contrary to the theory that guides some early education programs that focus solely on teaching letters and numbers, explicit efforts to foster executive functioning have positive influences on instilling early literacy and numeracy skills.

Early evidence from randomized trials of interventions designed to foster the cluster of executive function skills (working memory, attention, inhibitory control, etc.) indicates benefits in early literacy and math skills compared with children who experience “regular” classroom activities. Indeed, there is also evidence that emerging executive function skills contribute to early reading and math achievement during the pre-kindergarten years and into kindergarten. This is not surprising insofar as the acquisition of traditional academic skills depends on a child’s capacity to follow and remember classroom rules, control emotions, focus attention, sit still, and learn on demand through listening and watching. Neuroscientists are also beginning to relate specific aspects of executive functioning, notably attentional skills, to specific steps involved in learning to read and to work with numbers. It is important to emphasize that this research is in its infancy, and much remains to be learned. Not only do we need to understand the effectiveness factors that account for the emerging impacts on school readiness from interventions designed to focus on executive function skills, but we also need to examine whether effective early education programs that focus directly on social, numeracy, and language skills also have positive impacts on executive functioning. Thus, the highly interrelated nature of these capacities makes it difficult to label any single intervention as focused explicitly (or not) on the critical domains of executive functioning.

Contrary to popular belief, learning to control impulses, pay attention, and retain information actively in one’s memory does not happen automatically as children mature, and young children who have problems with these skills will not necessarily outgrow them.

The evidence is clear that, by 12 months of age, a child’s experiences are helping to lay the foundation for the ongoing development of executive function skills. These early abilities to focus attention, control impulses, and hold information “on-line” in working memory appear to be easily disrupted by highly adverse early experiences or biological disruptions. Evidence also shows that early interventions aimed at improving these capacities before a child enters school can have beneficial impacts across a broad array of important outcomes.

Contrary to popular belief, young children who do not stay on task, lose control of their emotions, or are easily distracted are not “bad kids” who are being intentionally uncooperative and belligerent.

Young children with compromised or delayed executive function skills can display very challenging behaviors for which they are often blamed. In most circumstances, however, it is the protracted development of the prefrontal cortex that is to “blame.” Efforts to help affected children develop better executive function skills and adjustments of the demands placed upon them to avoid overtaxing their capabilities are much more helpful than punishment for difficult behavior. Particularly when adverse experiences or environments elicit a toxic stress response, it can be very difficult for even the most competent children to enlist whatever executive function skills they have. In these circumstances, the provision of a safe and predictable environment offers the sense of security needed for successful behavior change to occur.